Author: Dana Nottingham

Date Published: January 28, 2022

Self-generated child sexual abuse material has created new challenges for law enforcement and others seeking to protect children from online harm. Not only is it a rapidly growing practice, with a 77% increase in websites with SG-CSAM from 2019 to 2020, but it is also becoming normalized among kids and young adults, creating a dynamic threat with the potential to seriously harm a child’s well-being.

What is Self-Generated Child Sexual Abuse Material?

Self-generated child sexual abuse material (SG-CSAM), also known as self-generated sexually explicit material, is “explicit imagery of a child that appears to have been taken by the child in the image” (Thorn). This imagery can be created both consensually (e.g. peer-to-peer sexting) or coercively (e.g. online grooming), and presents the unique challenge of not knowing which by merely looking at the picture or video alone. Even consensually created SG-CSAM leaves the child vulnerable, as once the child shares the imagery, they no longer have control over who has access, and their images can become content for child predators online.

The Complexity of ‘Nudes’ and Consensual Peer-to-Peer SG-CSAM

Before diving too deeply into SG-CSAM, it is worth discussing the impact of nudes (naked images) and their pervasiveness in the modern dating landscape, even with kids as young as 6th and 7th grade.

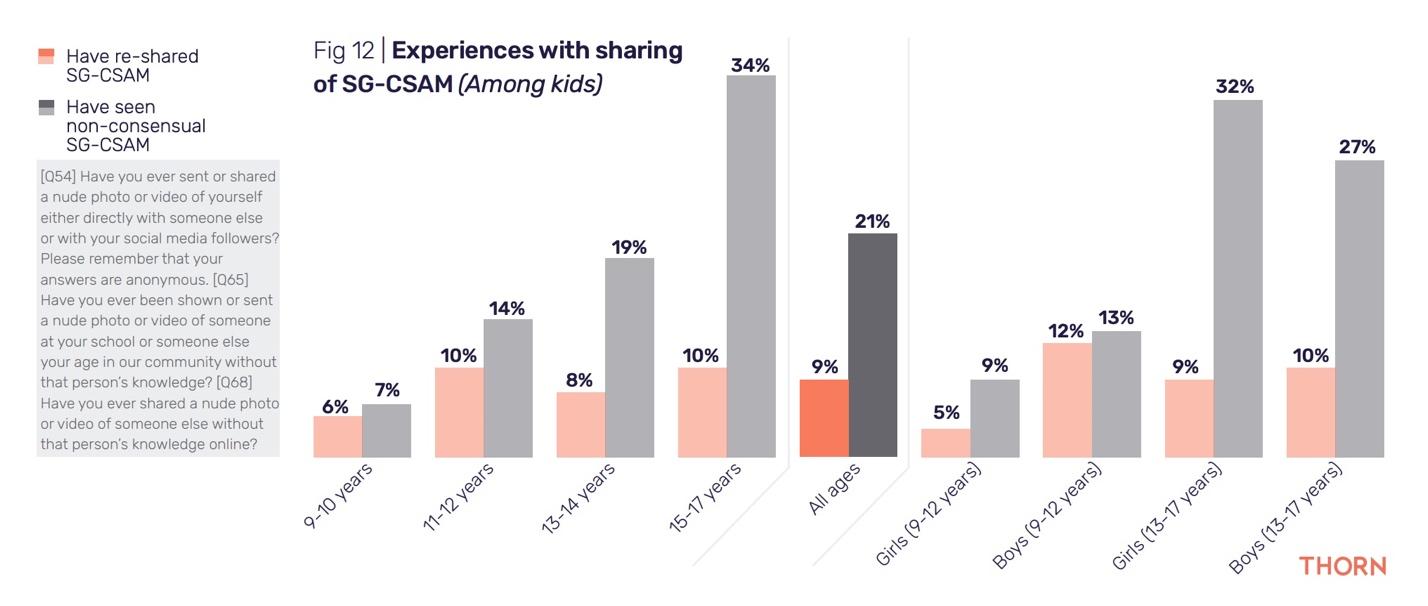

Thorn and the Benenson Strategy Group conducted a study on SG-CSAM in 2019 with more than 1,000 kids, aged 9-17, and 400 caregivers, with three major takeaways:

- It is increasingly common to create and share sexually explicit materials, with many kids viewing “sexting” and “sharing nudes” as normal.

- The experience of taking sexually explicit photos varies based on the conditions under which the photos were taken, and even those that were consensually created can quickly become harmful if they are re-shared beyond the intended recipient.

- Responses of victim-blaming, shame, and inaction can compound the harm and further isolate kids who are reporting abuse, or even prevent them from asking for help in the first place. (Thorn Executive Summary)

The study found that not only did 1 in 5 teenage girls and 1 in 10 teenage boys report that they had shared nudes, but nearly half of caregivers agreed that it is okay to share nudes when you are in a relationship with a person. Many respondents even noted it as a positive experience that made them feel closer to their partner. The sharing of explicit images is becoming increasingly common in relationships, and though many respondents noted that they were aware of the risk of non-consensual distribution, it is a risk deemed worth taking, with some even considering the act empowering.

However, this positive experience drastically changed when nudes were “leaked” or shared non-consensually. According to Thorn, “while the data suggests between 9% and 20% of teens have themselves re-shared someone else’s nudes, those being shown someone else’s nudes may be as high as 39%.” Once children lose control of their photos, there is a risk for viral spread and an increased vulnerability to threats and coercion. This is only made worse by the lack of confidence in websites removing images if they are reported and a high rate of victim-blaming, which we will discuss later.

Breaking Down Peer-to-Peer SG-CSAM in Schools

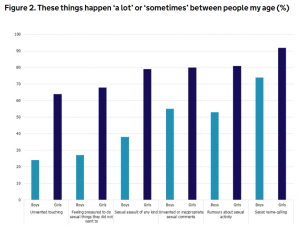

While it is worth noting the positive responses to consensually shared SG-CSAM, it is important to dive further into SG-CSAM’s negative effects, to better inform necessary monitoring and intervention and keep kids as safe as possible. A 2021 study done by Ofstead surveying over 900 children and young people across 32 schools in the United Kingdom found that a significant amount of harmful sexual behavior was occurring between students, both on and off campus, with much of it centered around SG-CSAM. This included recurrent requests for nudes, with some girls reporting that they would be contacted by as many as 11 boys a night. Many also reported receiving unsolicited explicit images from boys and men across social media platforms, including Snapchat, Instagram, and Facebook. It was so common that most went unreported. One woman, 18, was quoted saying: “Some girls do get it very often but it’s something you brush away because it’s not something you think of that’s out of the ordinary… and there’s nothing you can do about it.”

While it is worth noting the positive responses to consensually shared SG-CSAM, it is important to dive further into SG-CSAM’s negative effects, to better inform necessary monitoring and intervention and keep kids as safe as possible. A 2021 study done by Ofstead surveying over 900 children and young people across 32 schools in the United Kingdom found that a significant amount of harmful sexual behavior was occurring between students, both on and off campus, with much of it centered around SG-CSAM. This included recurrent requests for nudes, with some girls reporting that they would be contacted by as many as 11 boys a night. Many also reported receiving unsolicited explicit images from boys and men across social media platforms, including Snapchat, Instagram, and Facebook. It was so common that most went unreported. One woman, 18, was quoted saying: “Some girls do get it very often but it’s something you brush away because it’s not something you think of that’s out of the ordinary… and there’s nothing you can do about it.”

This normalization of sexual harassment was one of the report’s most significant findings: 80% of girls said that being pressured into sharing sexual images of themselves was experienced “a lot” or “sometimes” amongst their peers. The study found that adults in the school system tended to not realize the magnitude of the issue, due in large part to lack of reporting. Schools in which teachers and leaders were aware of the magnitude of the sexual harassment issue were also correlated to having open discussions on the topic as well as keeping records of past incidents.

There are a number of reasons that sexual harassment and violence went unreported, including:

- Lack of control: Students reported that not knowing what would happen next was a large factor in reporting, especially in places where previous responses had been lacking or too strict.

- Victim blaming: Similar to Thorn’s 2019 findings, being blamed and parents finding out were top reasons children didn’t report harmful sexual behavior, especially in cases in which drugs or alcohol were involved. They were also worried about being blamed for doing something they had expressly told not to do, such as sending nudes, even if they were pressured to do so.

- Normalization: Students were more likely to report what they perceived as severe incidents over incidents such as persistent requests for nudes, since they viewed them as so commonplace that there was no point.

Victim-Blaming

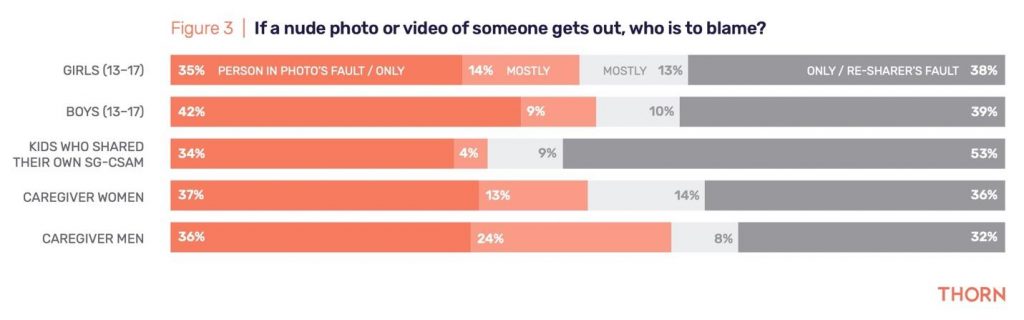

It is worth highlighting victim-blaming as it is such a pervasive issue that hurts and penalizes already vulnerable children. In the case of a nude image leak, 55% of caregivers and 39% of kids (including those who have shared their own images) exclusively blame the person in the leaked photo. Caregivers often respond with scare tactics and shaming, leaving the kids more vulnerable and even less likely to ask for help in the future due to fear of judgement, misunderstanding, or punishment.

If a child confides in you, express your appreciation for their trust and assure them that it is not their fault. This is an intensely difficult time for the child and it is vital to respond with kindness and compassion, rather than shame.

If a child confides in you, express your appreciation for their trust and assure them that it is not their fault. This is an intensely difficult time for the child and it is vital to respond with kindness and compassion, rather than shame.

Never download, screenshot, or share reported material.

If a child is in immediate danger, call 911. If a child is being harmed, make a report to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children’s CyberTipline. If you find a website promoting CSAM, or social media being used to spread child abuse content, report to The Innocent Lives Foundation.

Liability for Child Pornography

Another often forgotten risk of sharing explicit images is that both the child in the photo and the one sharing it are at risk of being charged with creating and distributing child pornography. Child pornography is defined under federal law as any visual depiction of sexually explicit conduct involving a minor, even if the child took the picture of themselves without coercion. Anyone involved in the picture or in its distribution could be liable under both state and federal laws.

Growth in 2021

Self-generated material is not only peer-to-peer; predators online can coerce children into creating and sharing images and videos, which are then circulated widely. The Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) reported that 2021 was the worst year on record for CSAM, with 15 times more material uncovered than in 2011. The fastest-growing increase in SG-CSAM came from children ages 7-10, more than tripling in number from 2020. This is in part due to the increased time spent online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has allowed predators to target younger and younger users on a larger scale.

“Children are being targeted, approached, groomed and abused by criminals on an industrial scale,” said Susie Hargreaves, IWF chief executive. “So often, this sexual abuse is happening in children’s bedrooms in family homes, with parents being wholly unaware of what is being done to their children by strangers with an internet connection.”

Creating a culture of shame around self-generated material will only decrease the likelihood that children will be willing to confide in their parents or other responsible adults in the case of victimization.

Conclusion

SG-CSAM is pervasive in our culture today and must be treated carefully, without creating a system of shame that will prevent children from coming to adults in the case of coercion or unauthorized sharing of private images. A common thread in both the Ofstead and Thorn studies was the importance of communication; having conversations creates a safe space for kids and shows them that they can speak to you without fear of being ignored or blamed. ILF board member and former FBI agent Robin Dreeke’s “TRUST” formula offers great insight into fueling those relationships. Moving forward, it will be vital to keep young voices in the conversation, or else risk falling behind in the ever-evolving digital landscape and allowing harm to come to vulnerable children.

Visit the Innocent Lives Foundation to report a case, learn more about how to keep your child safe online, or donate to support our efforts.